People gather in Prospect Park during the coronavirus outbreak in Brooklyn, New York City, March 27, 2020.

Andrew Kelly/Reuters

Related Video: How to Treat Mild Symptoms From Home

As countries across the globe approach and pass the peaks of their first waves of coronavirus infections, officials and experts are racing to figure out how to protect people long-term.

Individuals could gain immunity to the new coronavirus if they develop antibodies; that can happen through vaccination, or after they get infected and recover.

If enough people become immune, that can confer “herd immunity” to an entire population. This protects even people who aren’t immune, because so many others are immune that they prevent the virus from spreading within a community. Herd immunity would effectively end the coronavirus pandemic.

That day would come with the mass distribution of a vaccine, but that process is expected to take at least 18 months. Earlier in the pandemic, some governments also considered allowing herd immunity to develop on its own, without a vaccine, by letting the virus spread through their populations. But in its wake, the coronavirus would have left millions of recovered people with antibodies — but a trail of deaths would have followed, too.

Experts warned against this path.

“You don’t get herd immunity until you have a huge percent of your population that has had the disease,” Melinda Gates, cochair of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, told Business Insider.

She added: “We’re still a long way from herd immunity. And you can’t count on that, because a lot of people are going to die in the meantime if you let the experiment run and you just let the disease run its course in communities. Sure, we could get herd immunity, and we will get so much death.”

Story continues

How herd immunity works

Medical staff members pose for a group photo after returning home from Wuhan to help with the coronavirus recovery effort, in Bozhou, Anhui province, China, April 10, 2020.

STR/AFP via Getty Images

For a population to achieve herd immunity, a certain proportion has to be immune. That proportion depends on how infectious a virus is, a measure called R0 (pronounce “r-naught”). The R0 is the number of people the average person with a virus infects.

But R0 isn’t a fixed number. It can decrease if conditions change — specifically, if people stay too far apart for the virus to spread, or if so many individuals become immune that the virus can no longer spread from each person it infects.

The goal of herd immunity — as with all public-health responses to a new virus — is to bring the R0 below 1, which puts the disease in decline until it dies out. But the higher a virus’ R0, the more people need to be immune to make that happen.

For the coronavirus, the R0 is about 2 to 2.5, according to the World Health Organization.

average number of people that one person with a virus infects R0 scale

Shayanne Gal/Business Insider

“That is similar to pandemic flu of 1918, and it implies that the end of this epidemic is going to require nearly 50% of the population to be immune, either from a vaccine, which is not on the immediate horizon, or from natural infection,” Harvard University epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch told a gathering of experts on March 12.

We’re nowhere near 50% of the population becoming immune to the coronavirus, but it’s unclear exactly how far we are. In most parts of the world, experts don’t know how many people have had COVID-19 and recovered, largely due to limited testing.

Read more: Tests that can tell if you’re immune to the coronavirus are on the way. Here are the companies racing to bring them to the US healthcare system.

In countries like the US, where testing was scarce for weeks after early cases were detected, the most severe cases were prioritized for official diagnoses. People who have mild symptoms, or none at all, are still less likely to get tested — if they even seek testing in the first place. That means that many mild infections are not included in the counts of total cases or recoveries.

Not knowing how many people the virus has infected makes it more difficult to estimate R0.

Pursuing pre-vaccine herd immunity would have led to hundreds of thousands of deaths

Drone pictures show bodies being buried on New York’s Hart Island amid the coronavirus outbreak in New York City, April 9, 2020.

Lucas Jackson/Reuters

At the beginning of its outbreak, the United Kingdom’s government considered letting the virus spread through its population. As the UK case count passed 500 and the virus sickened health minister Nadine Dorries, schools and businesses remained open. Mass gatherings were still allowed.

The UK strategy was to “allow enough of us who are going to get mild illness to become immune,” Sir Patrick Vallance, the government’s chief scientific advisor, told Sky News. That, in essence, is the pursuit of herd immunity without a vaccine.

But on March 16, a report from the Imperial College London’s COVID-19 Response Team suggested that without preventive measures, COVID-19 could kill half a million people in the UK. That day, the government pivoted, advising residents to work from home and practice social distancing. Two days later, Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that all UK schools would close.

“The UK should not be trying to create herd immunity,” Dr. William Hanage, an epidemiologist at Harvard, wrote in The Guardian. “Policy should be directed at slowing the outbreak to a (more) manageable rate. What this looks like is strong social distancing.”

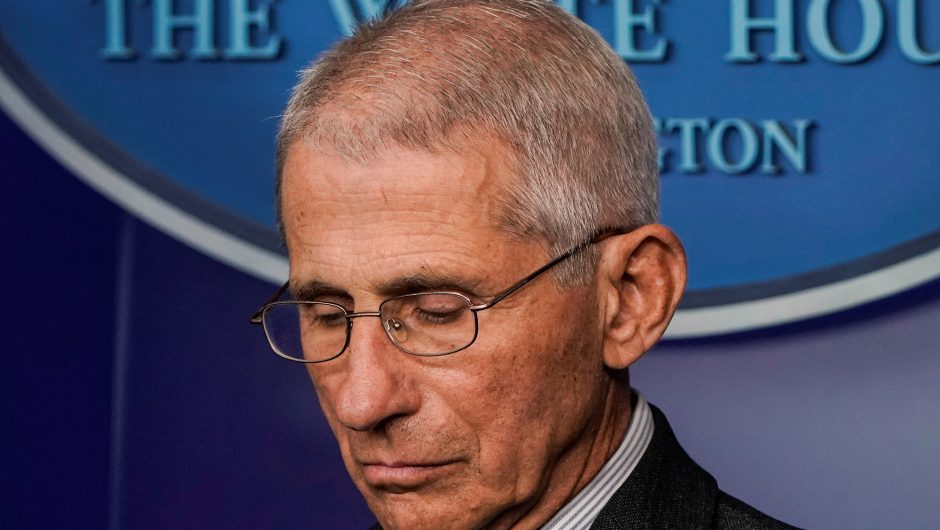

Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Dr. Anthony Fauci listens as President Donald Trump speaks during a coronavirus task force briefing at the White House, Saturday, April 4, 2020, in Washington.

Associated Press/Patrick Semansky

In a Situation Room meeting on March 14, President Donald Trump also suggested allowing the US to develop herd immunity, The Washington Post reported.

“Why don’t we let this wash over the country?” Trump reportedly asked Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

According to the Post’s report, Fauci initially didn’t understand what Trump meant by “wash over.” But when he realized, he became alarmed and laid out the likely consequences.

“Mr. President,” Fauci responded, according to the Post, “many people would die.”

Dr. Greta Bauer, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at Western University, has also debunked the idea of promoting a pre-vaccine “herd immunity strategy”.

She recently wrote in The New York Times: “Right now, too many people are getting sick through non-intentional spread, burdening hospitals and leading to severe illness and death. It is far too early to think about intentional infection as a strategy.”

Doubts about individual immunity

Farah Al-Awadi, a 28-year-old Iraqi woman who left quarantine after her recovery from COVID-19, wears a protective mask while her father kisses her at her home in Najaf, Iraq, April 1, 2020.

Alaa-Marjani/Reuters

It’s still unclear how much protection antibodies confer on people who have recovered from COVID-19.

Some early research suggests that not all recovered patients develop coronavirus-neutralizing antibodies to the same degree. According to a report from Chinese scientists that has not yet been peer-reviewed, about 10 of 175 participants studied did not develop neutralizing proteins. This suggests they could have a higher risk of reinfection.

What’s more, even a person who has some coronavirus antibodies might not be able to fight off an infection.

“We don’t know whether it will be possible to distinguish someone who is functionally immune from someone who has an immune response that’s not that protective,” Lipsitch told USA Today. “I think immunity is what’s going to get us through to the other side. And that’s the part that’s still the biggest uncertainty.”

Experts also don’t know how long immunity lasts, since the virus is still so new.

“We have not yet established that those who recover from this infection indeed develop long-term immunity,” Bauer wrote in the Times. “Herd-immunity projections depend completely on such a sustained immune response, and we haven’t found out whether that even exists. We all sincerely hope it does, but we won’t know for certain until we study recovered patients over time.”

Soldiers assigned to Javits New York Medical Station conduct check-in procedures on an incoming coronavirus patient with local emergency workers in the facility’s medical bay in New York City, April 5, 2020.

U.S. Navy/Chief Mass Communication Specialist Barry Riley/Handout via Reuters

The Korean CDC said last week that a group of 51 people who had recovered from the coronavirus later tested positive. China has reported similar incidents. But the KCDC’s director-general, Jeong Eun-kyeong, said it’s more likely that the virus reactivated in the 51 patients, rather than that they got reinfected.

“These apparent cases of reinfection may actually be remission and relapse, or false test results. However, researchers need more time to figure out what is happening with these patients, and the implications,” Bauer wrote in the Times.

Other experts have expressed more confidence in COVID-19 antibodies. Fauci said in an interview on “The Daily Show” that he was “willing to bet anything that people who recover are really protected against reinfection.”

But given the uncertainty around how many recovered people are truly immune and how long they’d stay that way, experts say that pursuing herd immunity without a vaccine isn’t wise.

“We want to get there slowly or, ideally, through vaccines,” Bauer wrote.

Tom Porter contributed reporting.

Read the original article on Business Insider