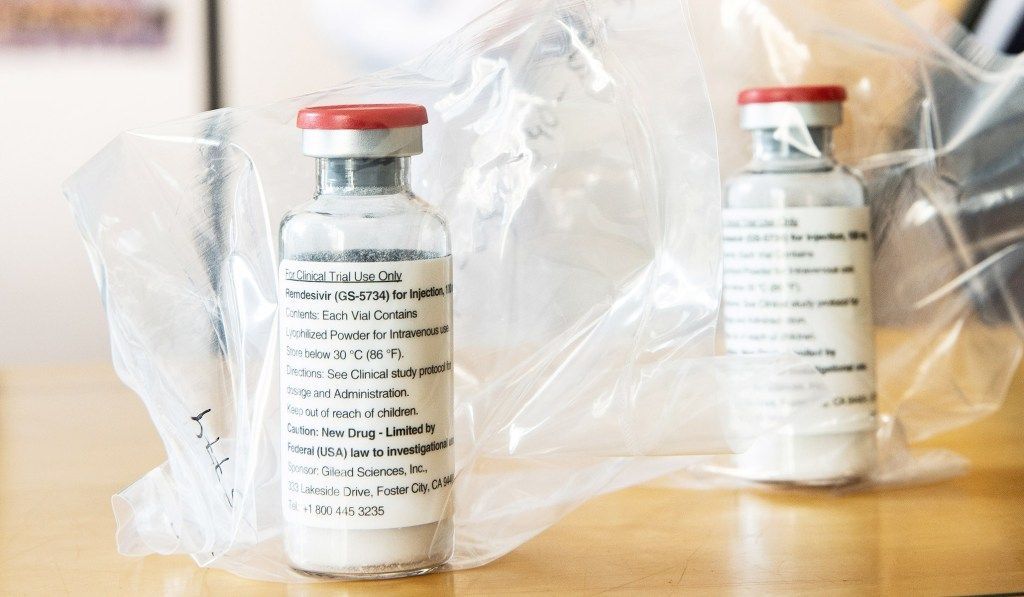

On Thursday, STAT News reported positive results from a clinical trial of remdesivir (RDV), a potential antiviral treatment for the coronavirus. Leaked data from a University of Chicago clinic participating in the study showed marked improvements in 113 COVID-19 patients with severe symptoms. Markets rallied on the news, with the Dow Jones and S&P 500 stock indexes jumping more than 2 percent. Shares of Gilead Sciences, the pharmaceutical company developing remdesivir, gained 10 percent when the market opened.

Remdesivir is a nucleoside analogue that works by inhibiting viral reproduction. Administered intravenously, RDV has a better safety profile than other drugs under consideration for COVID-19 treatment. Gilead initially developed RDV as a treatment for Ebola, and though it did not prove effective in that case, it works against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. If effective in humans, RDV would enable the rollback of physical-distancing measures and business closures. “Problem solved,” the stock-market rally seemed to say.

But the results leaked Thursday are far from definitive. The study in question is a “compassionate use” trial, in which experimental drugs are given to patients with severe illnesses prior to FDA approval. Compassionate-use studies do not include control groups of patients not treated with the drug, making it impossible to distinguish between the effects of RDV and the natural course of the illness. Gilead was quick to caution against reading too much into the preliminary results, saying in a statement that “the totality of the data need to be analyzed in order to draw any conclusions from the trial.” Indeed, the outcomes of the Chicago patients could be wholly unrelated to the treatment, and there is some evidence that the results are unexceptional.

As Harvard doctor Jeremy Faust pointed out, the trial treated patients in “severe” condition but not those in “critical” condition. Severe cases comprise those with a blood oxygen level at 94 percent saturation or lower, as well as those receiving oxygen support. Patients in critical condition, on the other hand, experience severe pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome. According to the trial protocol for compassionate use of RDV, in critical cases, “treatment with RDV might have only limited, if any, impact on the survival of the infected subjects.” Because RDV is meant to preempt the worst symptoms, the current studies exclude patients in critical condition.

Story continues

But only critical symptoms lead to death: A COVID-19 study from China recorded zero deaths of patients with severe symptoms. It’s possible that the patients in the Gilead trial would have developed critical symptoms, but it’s not certain. Based on a back-of-the-envelope analysis combining two studies of the clinical progression of COVID-19, roughly 9 percent of severe cases become critical, and approximately 3 percent of patients with severe symptoms die. These numbers indicate that of the 113 cases in the Chicago trial, around four were likely to die without a therapeutic. Two patients have died, which, albeit an apparent improvement, suggests only a statistically insignificant impact. That doesn’t undermine the efficacy of RDV; the sample sizes are small, and numerous unobserved variables affect medical outcomes. But that’s the point: It’s hard to conclude very much from compassionate-use studies.

What’s stranger about the exuberant response to the STAT report is that similar results had already been published. An April 10 study in the New England Journal of Medicine reported some positive outcomes of RDV use in a sample of 61 patients. Replication of those results at UChicago is encouraging, but it’s hardly a blockbuster.

Why did investors buy up Gilead stock on the news? Perhaps STAT’s framing of the news as an “early peek” at inside information excited markets. The vagueness of the story could be interpreted as a negative, because of the risk that the unpublished results are less rosy than they appear, but it could also be interpreted as a positive: What if the results are even better than we think?

Though still unproven, remdesivir shows promise, and we should all hope it works. Pharmacologist Donald Kirsch told National Review that RDV remains the therapeutic most likely to treat COVID-19 because it “targets the virus directly, unlike some of the other treatments such as anti-inflammatories that target the immune response.” A study released Wednesday found that the drug was effective in rhesus monkeys — another encouraging sign. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases launched a double-blind randomized control trial of RDV in February, which will provide better evidence of the drug’s safety and efficacy.

Until those results come out, we won’t know for sure how effective RDV is. Policymakers should continue to accelerate drug development and build capacity to administer drugs that work. But the likelihood of a COVID-19 therapeutic in the near future remains slim. Relying on a Hail Mary to reopen the economy is too risky. The White House guidelines for reopening, which emphasize contact tracing and building medical capacity, point in the right direction. While a COVID-19 drug would be a miracle, we should plan for a future without one.

More from National Review

Source link