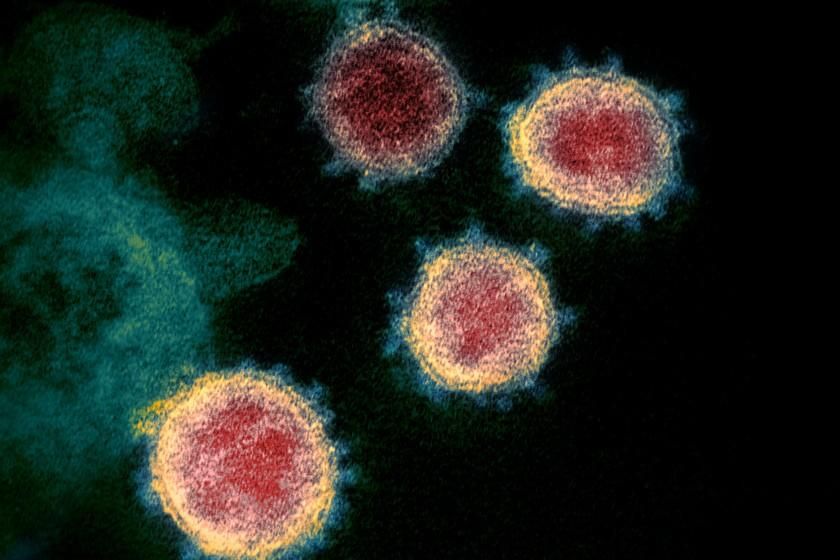

The coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2, which was isolated from a COVID-19 patient in the U.S. Scientists say there’s no evidence to support the idea that the virus escaped from a Chinese laboratory. (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases)

Like the virus whose origin it purports to explain, the following conjecture refuses to die: The novel coronavirus was cooked up in a Chinese lab and either escaped or was intentionally released.

It’s a claim without the support of any publicly available evidence. It implies that tight-lipped members of a large and malign network colluded to engineer the COVID-19 pandemic or to cover up an accident that caused it.

The story has all the earmarks of a conspiracy theory. And it has drawn support from the highest levels of the U.S. government.

By contrast, strong and widely available evidence supports a very different hypothesis about the virus’s origins: It evolved naturally.

Laboratory releases of dangerous viruses are not unheard of. In 2003, for instance, the virus responsible for SARS sickened a graduate student who worked in a Singapore lab a few months after the outbreak had ended there.

But there is nothing to indicate a similar breach touched off the current pandemic.

Scientists believe the direct ancestor of the coronavirus now known as SARS-CoV-2 has lived for so long in bats and other animals that it is no longer capable of making them sick. At some point near the end of 2019, the virus’s genetic code mutated in a way that allowed it to jump from its animal “reservoir” to its first human host.

At the time that leap was made, the virus had recently developed — or soon would develop — the ability to spread easily from human to human. The result is a global pandemic that has sickened at least 3.9 million people and caused more than 274,000 deaths.

Scientists cite several layers of evidence to support their surmises. Though they acknowledge gaps where further research would strengthen their position or shift their reading of the exact path the virus has taken, they are firm on where the evidence ultimately leads.

Here’s how a team of biologists, infectious disease researchers and biosecurity experts put it in a report published in the journal Nature Medicine: “We do not believe that any type of laboratory-based scenario is plausible.”

Story continues

To reach that conclusion, the authors drew on research that compared the genetic signatures of three sets of viral samples. The first were drawn from Chinese patients who became sick late last year with unexplained pneumonia; the second came from bats living near Wuhan, China, and which were sometimes brought to an open-air market for sale; and the third was from pangolins, mongoose-like animals from Malaysia that were known to have been illegally imported into China.

The analysis revealed a direct family relationship among the three. Bats were the likely origin of the coronavirus that appeared in Wuhan patients, but the virus neededed to undergo some key genetic shifts to infect humans. Mysteriously, many of the required changes were found in the more distantly related viruses from pangolins.

With an improbable amount of luck, a coronavirus might take on the mutations needed to infect humans while being cultured in a lab, the researchers conceded. More likely, nature simply made that jump once in the pangolin, and somewhere in the vast diversity of unsampled bat species, it appears to have done so again.

Meanwhile, other researchers who sifted through the genetic sequences of dozens of preserved viral samples found that the new coronavirus is a distant cousin of the coronavirus that caused the SARS outbreak of 2002 and 2003, and the coronavirus that gave rise to MERS in 2009. The virus responsible for COVID-19 has distinctive features that separate it from its predecessors by many, many generations, according to their report in the Journal of Virology.

But none of the genetic mutations looked like ones a scientific genius would engineer in a lab to tweak a virus for better performance, the researchers wrote. Instead, they have all the hallmarks of the gradual accretion of changes that occur over time as a virus encounters new environments and the immune systems of new organisms.

In other words, SARS-CoV-2 looks like a virus that has evolved, the team wrote.

Still other researchers examined the nearly 30,000 pairs of RNA letters in the virus’s genome and located the juncture where a mutation most likely changed its anatomical features.

The authors of the analysis in Nature Microbiology offered plausible natural circumstances to explain how it would have happened. For instance, they cited research showing that when chickens were repeatedly exposed to a harmless virus from swans, the virus developed mutations that made it capable of killing every chicken it infected.

They cited lab experiments to show how the virus’s changing shape would have allowed the organism to latch onto, infect and hijack human cells.

They detected biological strategies the virus had adopted that enabled it to spread from host to host — but just barely. The mechanism looked a lot more like the kind of hack that would evolve naturally in a coronavirus, not like the optimal solution a genetic engineer would choose.

And finally, they looked for the telltale signs of genetic tampering that would have been left behind by purposeful manipulation in a lab. These so-called reverse genetic systems are used in the making of coronavirus vaccines and treatments, and they have been described in detail in scientific reports. None are present in SARS-CoV-2, the investigators found.

All of this scientific work has been in the public domain since mid-March.

In recent days, however, President Trump and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo have breathed new life into the assertion that the novel coronavirus is the product of a state-run virology lab in Wuhan.

At the White House last week, a reporter asked Trump whether he had “seen anything” that gave him “a high degree of confidence that the Wuhan Institute of Virology was the origin of this virus.”

“Yes, I have. Yes, I have,” said the president, without offering further details. He then added, “and I think the World Health Organization should be ashamed of themselves because they’re like the public relations agency for China.”

Asked later that day to clarify what he had learned about the virus’s origins, he said: “I can’t tell you that. I’m not allowed to tell you that.”

Pompeo went further, telling ABC News on Sunday that “there is significant evidence this came from the laboratory” in Wuhan. He did not give any specifics, but added that he could not say whether the release had been intentional because “the Chinese Communist Party has refused to cooperate with world health experts.”

Those claims ran into scientific turbulence almost immediately.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, called the assertion that the coronavirus originated in a lab “a circular argument.”

“If you look at the evolution of the virus in bats and what’s out there now,” there’s a strong scientific case that “this could not have been artificially or deliberately manipulated,” Fauci said in an interview with National Geographic. “Everything about the stepwise evolution over time strongly indicates that [this virus] evolved in nature and then jumped species.”

The Office of the Director of National Intelligence had previously issued a statement to the same effect: “The intelligence community also concurs with the wide scientific consensus that the COVID-19 virus was not man-made or genetically modified.”

The World Health Organization’s representative to China weighed in as well.

“All available evidence to date suggests that the virus has a natural animal origin and is not a manipulated or constructed virus,” Dr. Gauden Galea said in an interview released by the WHO. “Many researchers have been able to look at the genomic features of the virus and have found that evidence does not support that it is a laboratory construct.”

However, Galea also said the global health agency has not been allowed access to laboratory logs from the Wuhan Institute of Virology or from China’s Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

China is an authoritarian state that competes with the United States in military, trade and diplomatic spheres, and relations between the two countries have become particularly testy since Trump took office.

As early as January, after China reported an outbreak of an unknown virus in Wuhan, the U.S. offered to send a team of epidemiologists to assist in investigating and containing the outbreak. China declined the offer, and has continued to hold the United States at bay.

In mid-February, China hosted a WHO-organized Joint Mission of experts on COVID-19. Dr. Clifford Lane, a key lieutenant to Fauci, traveled with the mission.

“It was very clear that the focus of Chinese scientists was on trying to find the reservoir” where the novel coronavirus originated, Lane said this week. They’ve also been looking for the pandemic’s patient zero, since they know that the closer they come to finding the first human to have been infected, the closer they’ll come to identifying the source.

“They don’t want this to happen again any more than we do,” he said.

Harvard microbiologist William Hanage said the facts do not support the idea that either a sloppy scientist or a mad genius tried to turn an existing coronavirus into a bioweapon.

“There is no way a person studying this in a lab would be able to identify the properties that have made it a pandemic,” he said. No scientist can peer into a virus’s genes and locate the features that have made it so diabolically successful at crisscrossing the globe, he said.

With a pandemic “beating at our door,” there’s nothing to be gained by talking about the virus’s origins right now, Hanage added. Whatever is said either “inadvertently fuels conspiracy theories” or “gets twisted into a political point, and that is unhelpful,“ he said.

His advice: “Focus on the raging pandemic and leave this for later.”