BARCELONA — Forget Spain’s stringent and painful three-month lockdown that started in March, crushing the economy, killing tourism and frustrating residents. Never mind the praise the country received as a model for dealing with the coronavirus, which through the spring had raged out of control, overwhelming hospitals and killing at least 28,000. All it took was a short summer — of jovial parties, bar hopping and vacation jaunts to coastal towns and neighboring countries — to return to something approaching the depths of the pandemic. As national health emergency coordinator Dr. Fernando Simón recently put it, “things are not going well.” In fact, it is going so not well, that some towns across Spain are locking down again, this time on their own accord.

Fernando Simón, Spain’s director of the Coordination Center for Health Alerts and Emergencies, speaks at a press conference on Aug. 31 in Madrid. (Oscar Gonzalez/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Public officials shy away from using the term “second wave,” although local and international media characterize it that way, but with new cases surging toward 9,000 a day, the highest numbers in all of Europe, Spain is not only the pariah of the Continent, it’s becoming a cautionary tale for the rest of the world, with a higher rate of new infections, per capita, than even the United States.

Where did this First World, resilient country go so horribly awry — and what does that mean for the U.S. as it deals with a series of regional outbreaks and a death toll stubbornly stuck at around 1,000 a day?

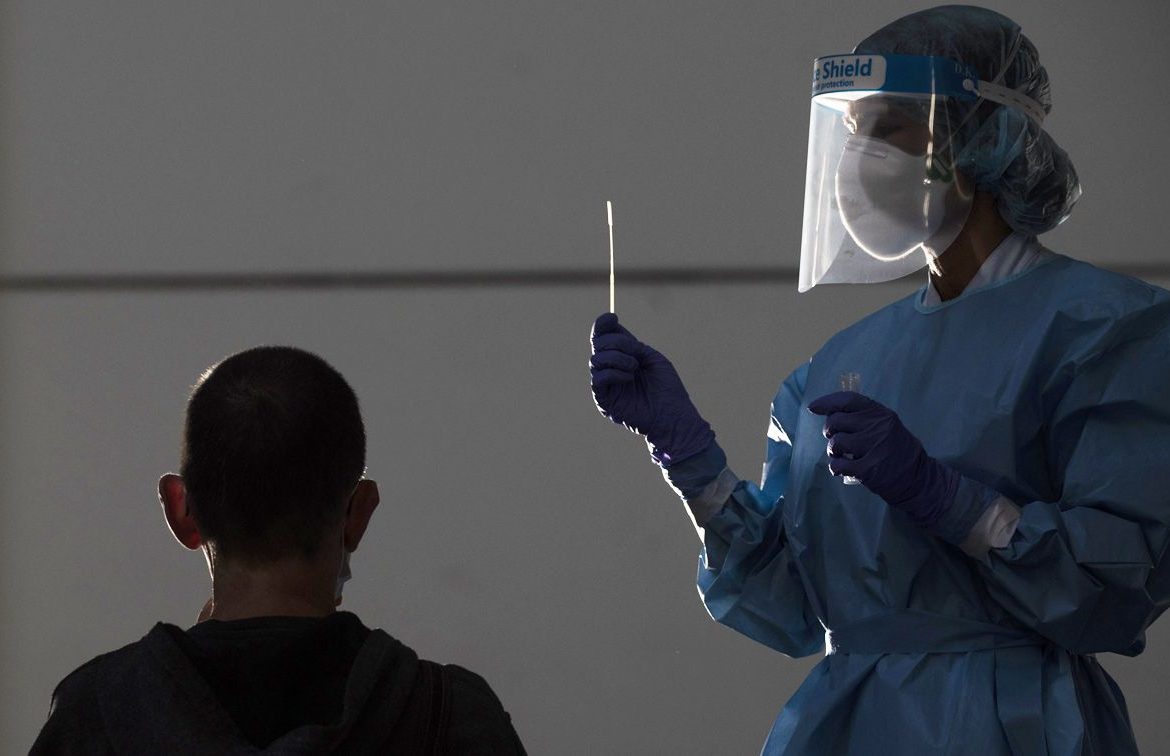

As is the case for Americans, few are rolling out the red carpet for Spaniards these days. Many airlines are canceling flights here — the list of those not touching down expanded this week — and Spaniards, or others who’ve set foot here, often have to show results of a recent PCR test (swab test) simply to board a plane to other lands, where they are often subjected to additional tests upon arrival — as well as two weeks of self-quarantine in some cases.

In the past few weeks, as the numbers kept rising, most of Spain’s fellow members of the European Union red-listed the country, warning their citizens to simply avoid it. Even France, where numbers of new infections are also rising quickly, though not at Spain’s rate, is talking about closing its border with its neighbor to the south.

Story continues

Summer vacations, tourists, youth, bars, gyms, nightclubs, large family gatherings, too much closeness, not enough contact tracing and increased testing of the general population have all been cited by health officials as factors in Spain’s remarkable spike, but they hasten to point out that the current situation, while worrisome, is not as bad as it was in March. While it’s true that in this latest resurgence, half of positives are asymptomatic and that death levels, while increasing to 50 or so a day, aren’t anywhere near what they were this spring, assurances like that of national Health Minister Salvador Illa this week that Spain “isn’t that different” than the rest of the EU ring hollow.

Vangelis Rosios, a civil engineer whose home is in northeast Spain, said, “7,000 or 8,000 new cases a day is too much — nearly as bad as it was during lockdown.” Rosios is currently trapped in Athens, since all of his airline’s flights back to Barcelona were abruptly canceled this week. “Today in Greece there are around 200 cases.”

Which is why it’s an apt moment to examine what Spain apparently is doing right and doing wrong.

A health worker does a PCR test on a patient on Thursday at a site in Irun, Spain, where mass coronavirus tests are being carried out. (Gari Garaialde/Getty Images)

Just as states in the U.S. all have different coronavirus policies, Spain’s 17 autonomous regions all have theirs. The political delineations weren’t an issue in March — when the situation was so grave that the national government in Madrid declared a “state of emergency” telling residents not to go out except for food and medical necessities. But in June, when the state of emergency was lifted, the national government tossed the job of managing the pandemic to the regional governments.

The result: mayhem.

Each region counts cases its own way — some using only positive PCR nasal swab tests, some adding in antibody results, some including suspected cases, as well as cases diagnosed at funeral homes — calculations that have sometimes resulted in numbers for one region being higher than those given for the whole country. Some regions designate three active cases from the same source as an outbreak; others define it as 10 people or more — rendering statistics like “488 outbreaks countrywide” — utterly useless. Sometimes regions report late or don’t report at all, resulting in headlines such as “Spain reports 958 new cases, not including cases from Madrid, Catalonia and Aragon” — in other words, excluding three of the five largest cities (Madrid, Barcelona and Zaragoza) in the country.

For residents following case counts, the situation is maddening as numbers often don’t add up, and for those looking for details, they are provided with migraine-inducing charts that might make one wonder if the point was to obscure the real numbers.

Even the figures for deaths from COVID-19 keep changing dramatically, going up and down — sometimes by thousands over the course of a day due to modifications in counting procedures; El País, Spain’s most widely read newspaper, recently calculated that the official COVID-19 mortality figure, currently more than 29,000, leaves out at least a third of the actual total, which is closer to 45,000.

As in the U.S., regional differences also played out over the utilization of face masks. When Spain reopened from lockdown on June 21, the national government issued a warning to mask up, which the regional governments interpreted as they wished: Catalonia, the northeast region of which Barcelona is capital, demanded that residents wear face coverings anywhere and any time they stepped out, while the regional government of Madrid required only that they be used on mass transit or when social distancing wasn’t possible indoors.

It’s worth noting that Madrid, which finally began mandating that masks be worn most everywhere only last month, now suffers the most cases in the whole country, with more than a third of new infections being reported in the capital — particularly worrisome as it’s the main transportation hub for Spain. The situation there is so concerning that health officials are considering imposing a lockdown on the capital city.

A group of people on a terrace on the day the Ministry of Health decreed the closure of nightlife, as well as the obligation to close restaurant premises at 1 a.m., on Aug. 14 in Lugo, Spain. (Carlos Castro/Europa Press via Getty Images)

Besides, even with regulations in place, some regional and municipal governments barely bother to enforce them. Never mind that not wearing a face covering outdoors in Barcelona is punishable by a 100-euro fine; it isn’t uncommon to see the maskless stroll right past police, with no repercussions. Overall, mask use is indeed up; the Spanish media recently boasted that Spaniards were the best in the world for wearing so-called mascarillas. The problem is where they are worn: the elbow mask was a popular fashion this summer, and the chin mask remains ubiquitous.

And even though social distancing is theoretically imposed everywhere — restaurant tables must be at least 6 feet apart — partiers often crowd six, eight or more around one table. “I find it contradictory,” says Barcelona documentary maker Tom O’Flynn, “that everybody wears masks on the street — and then takes the masks off to cram into a crowded bar.” He adds that unlike in Portugal, where restaurant workers wear masks, gloves and tote hand sanitizer on a belt, in Spain it’s common to be served by waiters with masks at half-mast, covering only their mouths, if that.

What’s more, Spaniards, a warm, affectionate nationality, are loath to drop their most common greeting, the double-cheek smooch. Not until August did the Health Ministry warn against it as a potential kiss of death, months later than other Mediterranean countries. By midsummer, family gatherings were accounting for 40 percent of new cases.

In August, as the number of cases began ticking up and the median age started dropping — it’s now 33 — health authorities began pointing fingers at young people socializing in gatherings lubricated with alcohol. Some regional governments threatened a 15,000-euro fine for botellónes, the bottle-sharing shindigs on beaches and in parks. Dance clubs and gyms were forced to close for a few days, and bars had to shutter at midnight; predictably, given the contradictory messaging lately, many of those orders were soon tossed out by the courts.

Spain has also dramatically fallen down on the job of contact tracing, widely regarded here as a violation of privacy. Beyond the dearth of “tracers,” and the fact that plenty of those testing positive aren’t queried about recent whereabouts, those who are asked to name recent contacts complain that they don’t want to give up the names.

In response, the government has deployed several thousand military personnel to various regions to augment the contact tracing effort. A new COVID-19 app that anonymously notifies those who may have been exposed is being rolled out. But that won’t address the Spanish reluctance to stand 6 feet apart, or to stop kissing people they meet. There are alternatives — the Thai wai, a small bow with the hands together; the fist bump; the elbow rub — but the affectionate practice that’s as central to the culture as the tapas bar shows few signs of waning.

_____

Read more from Yahoo News: