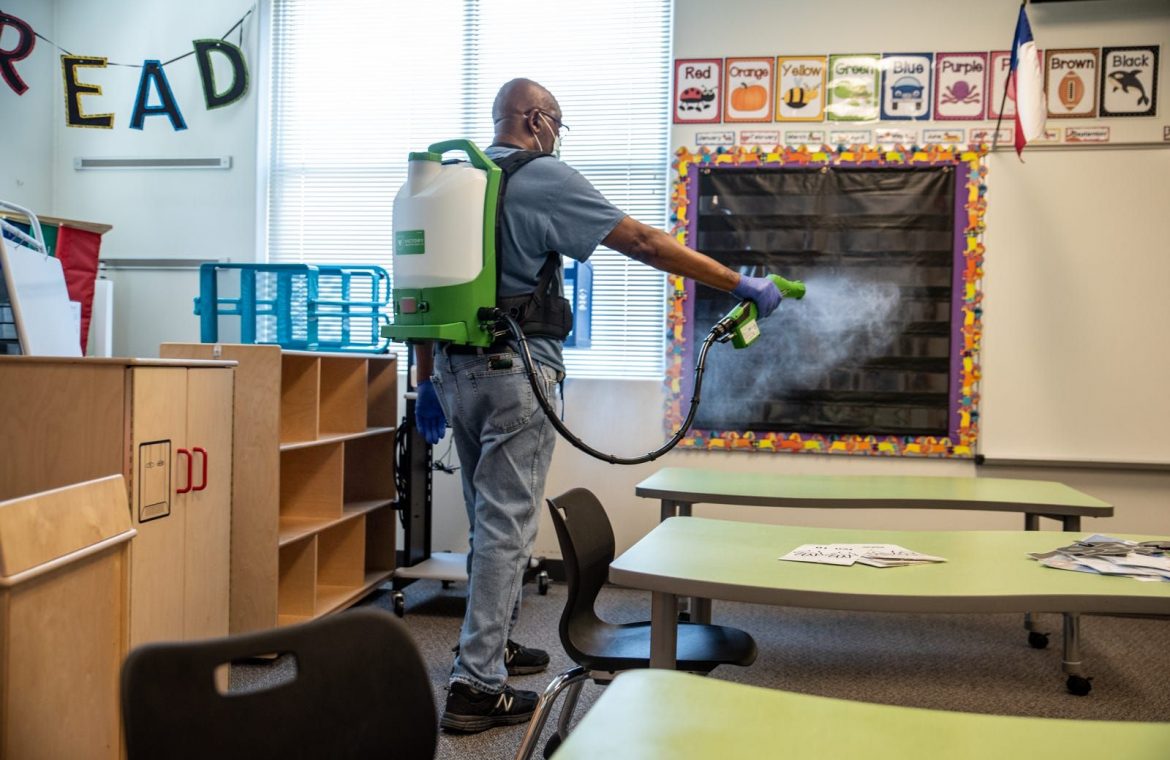

Thousands of American parents have already sent their children back to the classroom and millions more will soon join them amid fears about the raging pandemic and whether they’ll even be notified when coronavirus hits their campuses.

School districts, health departments and state agencies across the country have provided mixed messages about whether they will release information about coronavirus cases in students, teachers and staff at K-12 campuses.

Reporting by the USA TODAY Network also found little consistency in how schools and health departments plan to coordinate information and what, if anything, they will tell the broader public.

Many of these gatekeepers have pointed to medical and educational privacy laws as reasons to withhold even basic counts of coronavirus cases. That’s despite federal guidance saying those laws aren’t barriers to disclosure and legal experts who note that schools can share information as long as they don’t identify individuals.

In Florida, Martin County teachers recently heard rumors that a school employee died from COVID-19 just days before the start of in-person classes. District spokesperson Jennifer DeShazo confirmed the death but not the cause, citing HIPAA, the federal privacy law that applies only to medical providers releasing identifying information.

In Indiana, the Evansville Vanderburgh School Corp. cited the same law as a reason its website shows only county-level case data but not information about cases in the district or particular schools. On Friday, the district said it wanted to share information but was waiting on state guidance.

“I want a measurable way to tell me if they’re doing a good job protecting my kid or not,” said Jeff Anderson, whose two sons attend school in Evansville. He said he deserves to understand how elected officials are making their decisions.

In Missouri, North Kansas City Schools Superintendent Dan Clemens said he would be “imposing on the privacy rights of individuals” by reporting any coronavirus cases in a district with so few people, according to a story by KCUR.

Story continues

In Tennessee, officials initially said they had no plans to even track information on school-related outbreaks much less share information about them with the public, but then they changed course under public pressure. Gov. Bill Lee said the state would have a plan to allow schools to publicly share the number of COVID-19 cases at their facilities.

“I believe that we have to protect privacy but we also have to be transparent,” Lee told reporters on Aug. 4.

A fine balance

Legal experts and government transparency advocates say schools, as a whole, have a long track record of abusing privacy laws to keep information secret and force the public to enter costly lawsuits to gain access to records.

Justin Silverman, who leads the New England First Amendment Coalition, said several states also had cited HIPAA as a reason for withholding coronavirus case counts at nursing homes, although many later reversed course and released that information.

Although there’s a fine balance between the public’s right to know and personal privacy, many health experts said clear and consistent disclosure of even basic case numbers is essential for sound decision-making.

Dr. Nathaniel Beers, who serves on the American Academy of Pediatrics Council on School Health, suggested districts should have a tiered communication approach: providing the most detailed information to people with direct exposure; a more generic notification with health screening guidance for others in the school; and basic information on case counts and response for the general community.

Liz Guidry working alone in her classroom preparing for when students return to school at Our Lady of Fatima Catholic School in New Orleans, Tuesday, July 28, 2020.

“For schools to be open, you need staff to feel like safety is first. You need students and parents to feel safety is first. You need the broader community to feel like the school is taking care of business and not putting everyone else in harm’s way,” said Beers, who also is president of the HSC Health Care System in Washington, D.C. “That’s where the broader communication is really critical.”

Standing guidance from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services says that HIPAA does not apply to elementary and secondary schools.

In particular, the agency notes they are “not a HIPAA covered entity,” which means they do not provide health care services reimbursed by Medicare or Medicaid. Even if they did, the school would maintain the details in education records that are separately protected by FERPA, the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act.

But even FERPA does not bar schools from releasing details about coronavirus cases, the U.S. Department of Education said in its own guidance in March. Schools can provide basic information to parents as long as it doesn’t identify specific students.

The education agency also said the need to act on a health emergency might outweigh personal privacy in some cases. As an example, the memo said schools might need to share identifiable information, including the affected person’s name, with members of a wrestling team if someone on the squad contracted COVID-19.

“In these limited situations, parents and eligible students may need to be aware of this information in order to take appropriate precautions or other actions to ensure the health or safety of their child or themselves,” wrote the agency.

Neither HIPAA or FERPA bars schools from releasing such information about school employees.

Attorney Frank LoMonte, who has defended student rights to free speech and public records for decades, lauded parts of the federal guidance as an appropriate balance between personal privacy and the public’s right to know how their governments are making decisions.

“It’s totally proper for schools to be telling parents the number of cases,” said LoMonte, who also leads The Brechner Center for Freedom of Information at the University of Florida, “and even, in exceptional cases, to reveal details about the individual afflicted student if there has been close physical contact, if that information is necessary for the health of others.”

The memo noted that schools should not share personally identifiable information with the media, but LoMonte noted that neither FERPA or HIPAA prevents schools from sharing non-identifiable information with the media and the general public. He worried that school leaders might be confused on that fact because it was not specifically stated in the agency’s guidance.

“That was a very poor choice that is only going to foster more confusion,” he said, “but it’s totally consistent with the Department’s decades of disregard for public oversight of schools.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Schools cite HIPAA to hide coronavirus numbers. They can’t do that.